A Political Bubble, Burst

This story originally appeared in the fall 2018 issue of The Scranton Journal.

In the Jesuit tradition, students practice listening to understand in a recent civic engagement initiative to bridge the political divide.

Students arrive on campus each fall with distinct, sometimes very personal stories that have shaped their evolving political identities. In today’s polarized environment, their instinct might be to engage only with those like-minded or, in class discussion, to shy away from sharing their experiences or their values. The result is lost opportunities.

“At a time when talking to people with different political views seems like a dying art form, Scranton’s strong campus community — with its Jesuit emphasis of care for the other — has made this kind of challenging engagement possible,” said Julie Schumacher Cohen, director of Community and Government Relations at the University, whose office coordinates a collaborative new initiative at Scranton called “Bursting Political Bubbles: Dialogue Across Differences.”

The initiative aims to bring students together, outside of class but in connection with academic courses, to share their personal experiences and beliefs — and, more important, to listen to others — in a space that is confidential and respectful and open to the unexpected and uncomfortable. Using a method called Reflective Structured Dialogue conceived of by Essential Partners, a nonprofit organization based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, that helps “foster constructive dialogue where conflicts are driven by differences in identity, beliefs

“A lot of times we tend to put a certain view on another group — that they are liberal or conservative — then we think, ‘Well, they definitely believe this or believe

The initiative has campus-wide involvement, run by a Campus Working Group.*

“These dialogues are about better understanding where other people are coming from, understanding where the person’s belief system comes from and, ultimately, building empathy,” said facilitator Teresa Grettano, Ph.D., faculty member in the English and Theatre Department, who in the 2018-19 academic year is coordinating a Clavius seminar for faculty and running an academic course as part of the initiative.

Learning to listen

Each political dialogue session — three in the spring of 2018 — was structured carefully. After opening sessions to understand biases and present the “rules” of communication, including respecting others’ stories and perspectives, students broke up into smaller groups, and facilitators followed a consistent format to ensure the students did the talking. And the listening.

“It takes you out of your own little bubble,” said Harvey, who attended two of the three sessions in the spring. “We all surround ourselves with people who agree with us constantly. We never really listen to dissenting views. And if there are dissenting views, we either unfollow them on Facebook or unfriend them. The sessions allowed us to share our own views but also be open to listening to what everyone else was sharing.”

Listening. It’s not a new idea. Here is St. Ignatius of Loyola in 1546 speaking to the fathers attending Council of Trent: “Be slow to speak, and only after having first listened quietly, so that you may understand the meaning, leanings and wishes of those who do speak. Thus, you will better know when to speak and when to be silent.”

“We put together the practical facilitation skills from Essential Partners with the spiritual guidance of St. Ignatius of Loyola. Together, they create an environment where students can begin to engage with genuine curiosity and conviction, honesty and humility. It’s not about glossing over differences or staying neutral — in fact, the dialogue process can make you a more effective advocate. It’s not easy, though,” said Schumacher Cohen.

Enis Murtaj ’20 said he knows he should listen, but he thought it was effective to have the rules set out so that people — including him — did.

“It’s useful to listen for the sake of listening, not listening for the sake of responding, which a lot of people do in this day and age,” he said. “And I’m guilty of it, too. The rules made you listen to other people’s opinions, which makes you understand them a little better because you’re actually hearing where they’re coming from.”

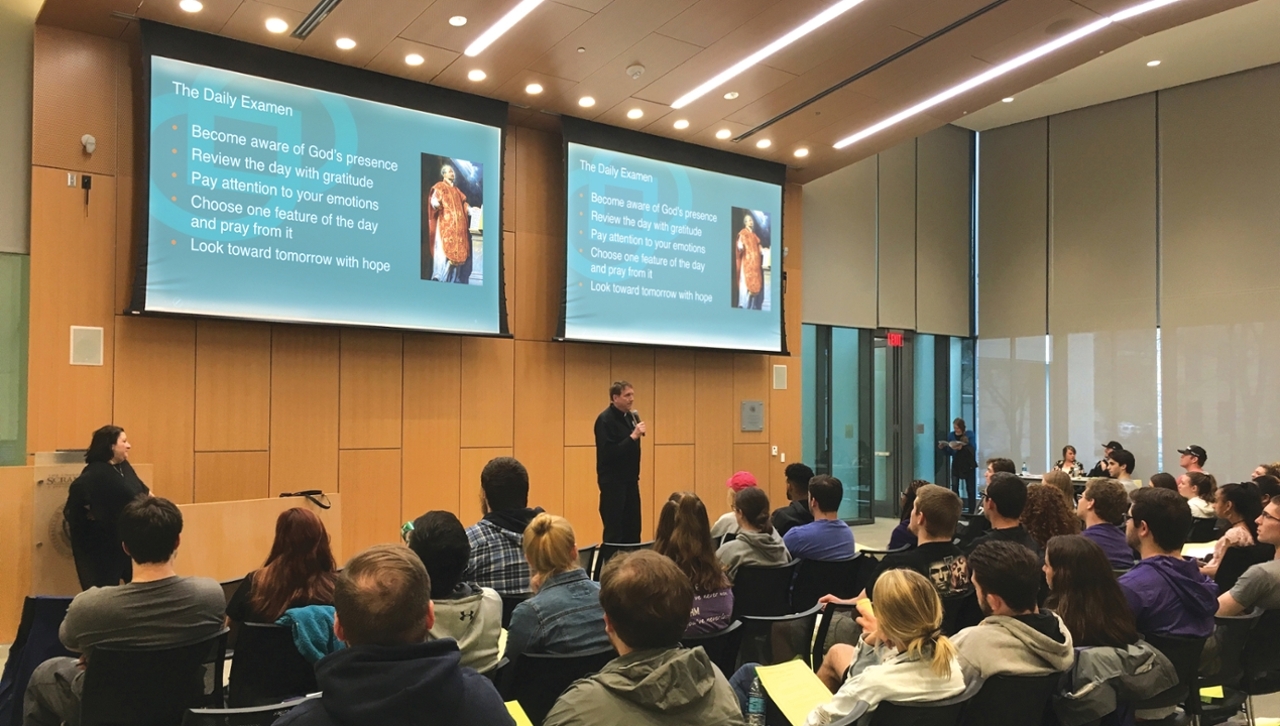

By reading and discussing the Daily Examen, Patrick Rogers, S.J., a facilitator and the director of the University’s Jesuit Center, urged students to be present and reflective in discussions about their political values, guns and immigration, topics that, in class, might be uncomfortable or even off limits.

“When we use the reflective structured dialogue method we are putting our thoughts about the topic being discussed into a larger context that actually is ‘built’ so that people know that there is room for differing opinions and that we don’t have to ‘solve’ each other,” he said.

Students and facilitators agreed that it was sometimes against their instinct to stay quiet, to not interject, when a student was talking. It was di cult, too, to hold back from sharing their view in response to someone else’s view.

Murtaj found it particularly difficult, as he is a self-proclaimed debater. “I had to hold back a little,” he said. “We had agreed to respecting each other, not talking over each other. It made the environment open.”

That “open” space is crucial in a reflective structured dialogue so that all students have the same amount of airtime, said facilitator Jessica Nolan, Ph.D., associate professor of psychology. “The reflective dialogue helps to accomplish the goal of creating groups of equal status,” she said.

Continue reading this article in the fall issue of The Scranton Journal, here.