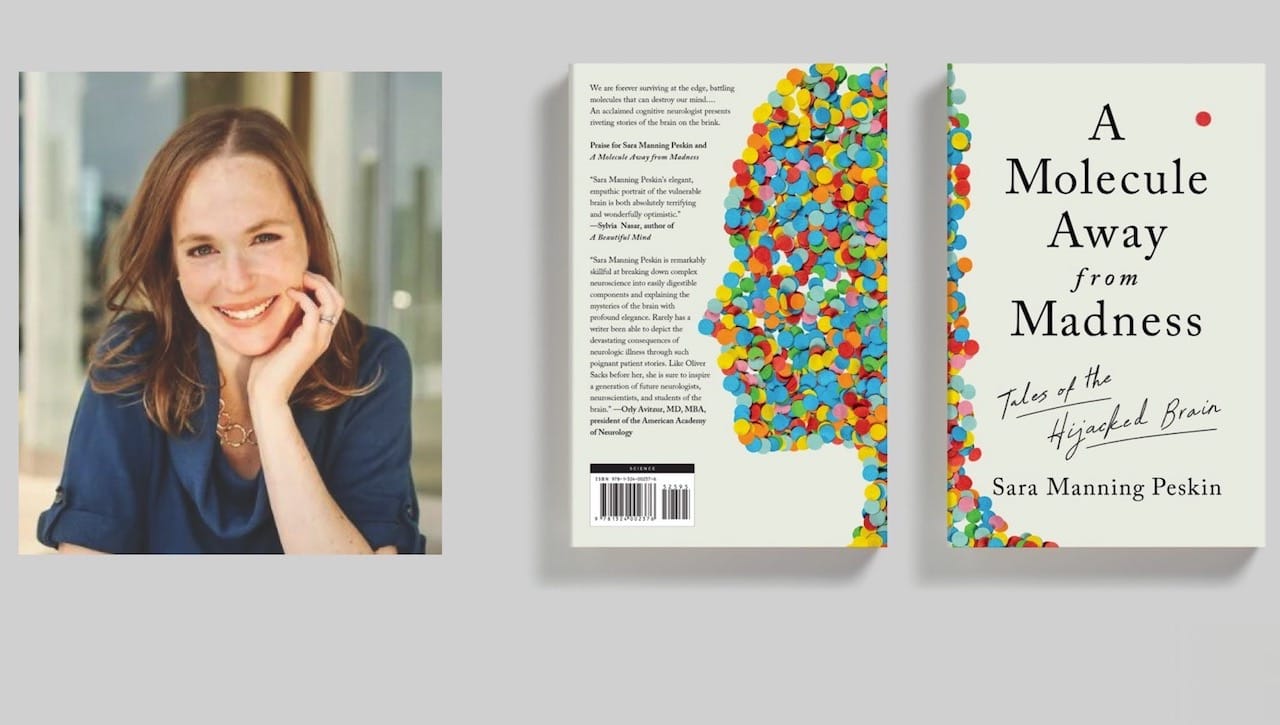

Author Discusses Book ‘A Molecule Away From Madness’

By, Bethany Belkowski ’24, student correspondent

The University’s Schemel Forum welcomed Sara Manning Peskin, M.D., assistant professor of clinical neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, as guest speaker for the Nov. 2 World Affairs Luncheon Seminar. Dr. Manning presented excerpts from her book, “A Molecule Away From Madness: Tales of a Hijacked Brain,” outlining the ways in which the molecules necessary for human survival can sometimes also sabotage human brains/bodies.

Dr. Manning began by defining molecules as groups of fundamental building blocks bound together into units that can then play integral roles in the functioning of one’s body. She continued, explaining that researchers have noticed that single molecules can cause ailments like cancer. In turn, cancer can be treated or even eliminated with targeted solutions that specifically attack the molecular causes. With this knowledge, Dr. Manning argues in her new book that “a similar molecular approach will likewise yield solutions to cognitive aliments that plague our brains.”

To begin her exploration of cognitive diseases that could be tackled with targeted solutions, Dr. Manning divided cognitive diseases caused by molecules into four categories: “Mutants” (typos in DNA), “Rebels” (proteins that begin targeting the brain), “Invaders” (small molecules that cause problems by being present when they should not be), and “Evaders” (small molecules that cause problems by not being present when they are needed).

Dr. Manning continued, outlining several anecdotes regarding Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia. She explained that single molecular mutations of DNA can be responsible for extreme cases of Early Onset Alzheimer’s disease or can predispose individuals to the development of dementia. Similarly, with Pick’s disease (another disease of cognitive degeneration), 20 percent of cases have been found to be caused by a single genetic mutation. Proteins (often rebellious kind of molecule) can also overproduce in areas of the brain or within the communication network of the nervous system, causing autoimmune diseases and other forms of dementia. However, as Dr. Manning stressed, with the right targeted treatment, these ailments can potentially be entirely eliminated.

In another anecdote from her book, Dr. Manning gave an example of a molecular invader. She explained that, in its earlier forms, general anesthetic would sedate patients to the point that they would stop breathing. In turn, doctors would have to manually help a patient breathe while they operated. In an effort to find a better anesthetic, researchers discovered a compound that worked well in animals, so it was rapidly approved for human use by the FDA. However, when patients were administered this general anesthetic, its dissociative effects would sometimes last for two days and sparked violent tendencies in individuals. The anesthetic was recalled and researchers learned that the molecule, when present in the brain when it should not be, cut humans off from reality, leaving only their thoughts to create what an individual would then perceive as reality. Today, this compound is better known as PCP.

In a final anecdote, Dr. Manning described a molecular evader that the human brain suffers without. Pellagra, a disease that causes dermatitis, diarrhea, dementia and eventually death, appeared in the Southeast United States in the early 1900s. It mostly arose in prisons, orphanages and rural farm areas, but began spreading rapidly. The government dismissed it as an infection contracted by society’s unclean. However, Dr. Joseph Goldberger, a researcher convinced that the disease was connected to diet, went to great lengths (including ingesting a pill composed of an infected patient’s excrement and dermatitis scales) to demonstrate that the disease could not simply be caught. In proving this, Dr. Goldberger allowed for the later discovery of the body’s need for Nicotinic Acid (B3 vitamin), which impoverished people often lacked in their grain and corn-heavy diets. Now, there is a simple drugstore solution to supply the molecule the body so desperately needs.