Professor Emeritus to Study ‘Sacrificial Ant’

Literature, legend and lore have long held up the humble ant as a model insect citizen. Industrious, organized and future-focused, the tiny creature has a stature grown from its work ethic.

Most people know the famous fable, penned by Aesop, titled “The Ant and the Grasshopper.” As the grasshopper whiles away the summer playing music, the ant busies herself procuring and storing food for winter. When winter arrives, the hungry grasshopper humbly begs for a bite from the scornful ant.

The tale has long sparked debate. Which was truly the wiser creature? And are ants as generous as scientists would have us believe?

That’s one basic question on the mind of University of Scranton Professor Emeritus John R. Conway III, Ph.D., a sought-after authority on a type of inarguably benevolent southwestern and Mexican honey ant (species name is mexicanus) that, in essence, has some greatly swollen workers, called repletes, that live to eat, as much as possible, not for personal pleasure, but for the very survival of the colony.

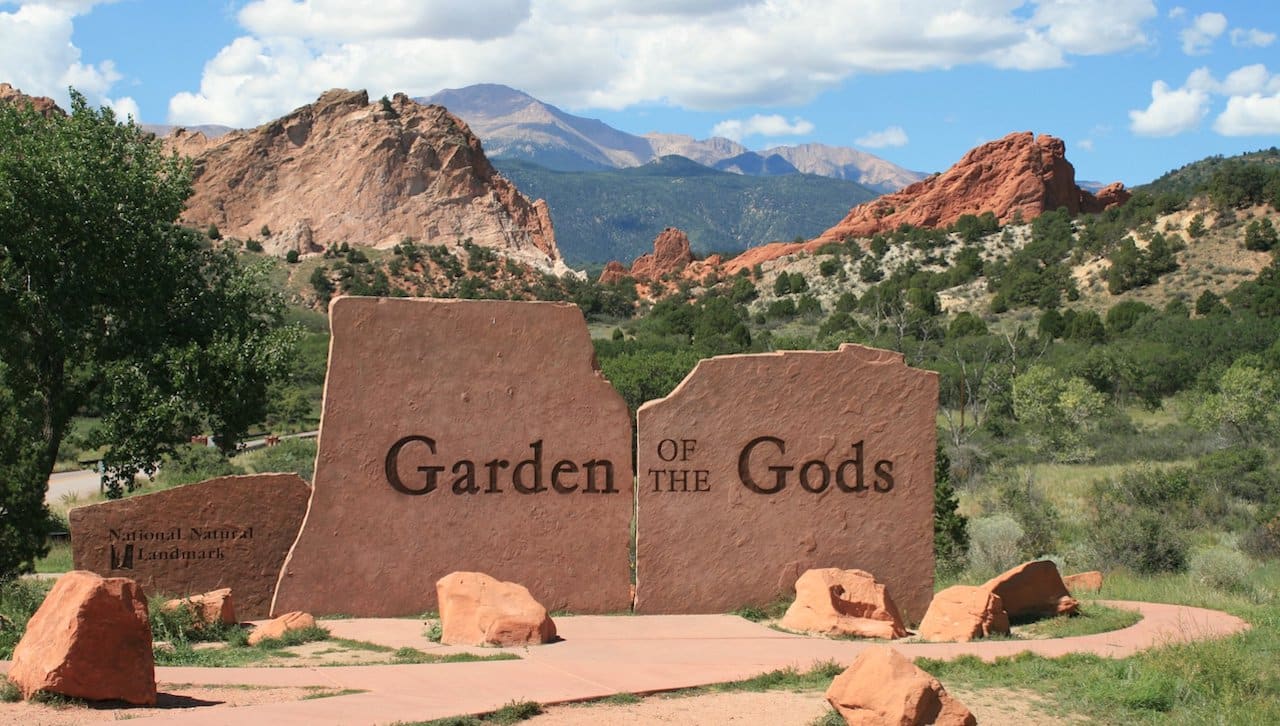

Dr. Conway’s original 1975 doctoral research on this fascinating ant has retained its relevance for more than four decades. In fact, owing plenty to increased visitor interest in his original research spot – The Garden of the Gods near Pikes Peak – the city of Colorado Springs recently awarded him a $30,000 grant to pick up where he left off.

The background story puts the renewed interest in better context.

The role of a honey ant replete might initially seem enviable: Hang around all day, from the ceilings of specially-constructed underground chambers, and ingest food regularly delivered by other colony workers.

But any images of a life of leisurely excess quickly disappear. Turns out all the hanging around happens because the honey ant repletes, whose abdomens can swell to the size of grapes, can do nothing else and become so engorged they can barely move.

“They spend their whole lives there, prisoners in their own nests, due to their immobility and the small size of the passageways” Dr. Conway said.

Their sole role is to function as living larders, storing food that otherwise would run scarce in arid, or semi-arid climates. Eventually, the honey ant replete, once fully swollen with stored sustenance, is drained.

And there’s the rub.

“As far as we know, once they are drained, they die,” Dr. Conway explained. “So they essentially sacrifice their lives for the good of the colony.”

The process, and these very unusual ants themselves, are cause for intense curiosity, in the scientific community and among the general populace, especially visitors to The Garden of the Gods, where the Rev. Henry Christopher McCook did the first extensive study of honey ants in 1882, Dr. Conway said.

“He was the first one to describe what was actually going on in some detail,” Dr. Conway said, explaining that’s why the Garden of the Gods was the first place he himself went when he decided to pick up McCook’s mantle and study this species of honey ant as part of his Ph.D. research while at the University of Colorado in Boulder.

“I wanted something that was not only of academic interest, but also of popular interest. I was interested in photography and had National Geographic and other popular scientific magazines in mind. Fortunately, I have been able to achieve that,” said Dr. Conway.

Now Dr. Conway, who served as a biology professor at The University of Scranton from 1985 through to his retirement in 2016, can add to his achievements as he revisits his work, especially to compare nest numbers and provide updated data to the city of Colorado Springs.

“They want to see if the number of colonies has increased or decreased and seek my advice on preservation of this unusual ant species for the future,” Dr. Conway said, noting, “One of my main chores is to see if I can relocate the nests I found in 1975.”

He has a vast collection of topographical maps and aerial photographs marking his original nest locations that he hopes will aid him.

If successful, Dr. Conway said, he will have a whole new set of data on how long nests can survive.

Dr. Conway, a world traveler, who during his Scranton tenure also received grants to study in Arizona and the Australian Outback, looks forward to returning to Colorado, but also will miss The University of Scranton and the other places it took him. In Australia, he led Earthwatch expeditions to study another honey ant, Camponotus inflatus, that independently evolved the same adaptation of storing nectar in swollen hanging repletes. Additionally, he investigated the use of these ants in the diet and culture of Australian Aborigines and found that they are still important in the Dreamtime of some tribes who paint them and have honey ant songs.

“One of the things I look back most fondly on from my time at the University was leading tropical biology trips to places such as Belize, Guatemala, Jamaica, Costa Rica and Panama every other intersession,” he said.

Currently, he is also working on lectures and a book on the biologists and naturalists who discovered the approximately 2 million known plant and animal species that constitute the Earth’s incredible biodiversity.