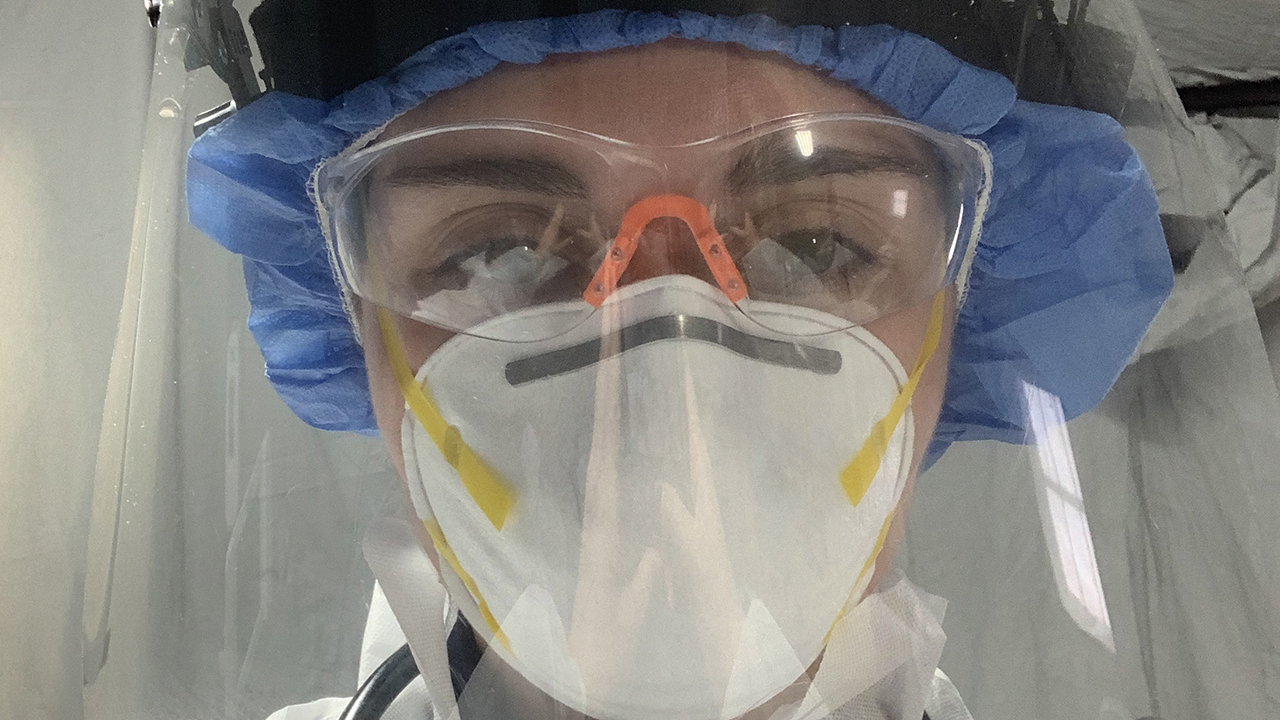

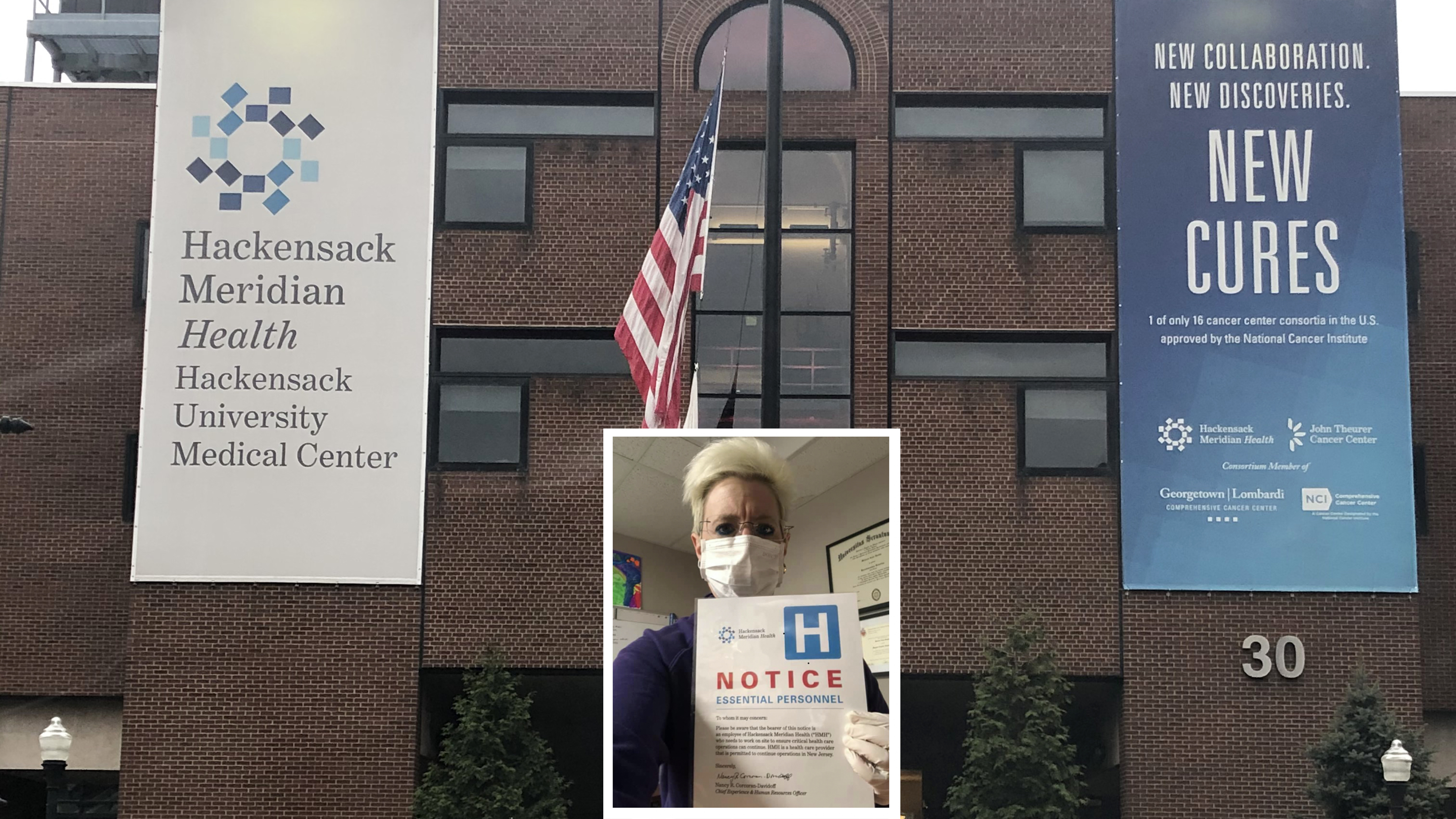

Hear from Kelly Sarti Wroblewski ‘02, director of infectious disease programs for the Association of Public Health Laboratories, about the COVID-19 testing landscape.

WHO: Kelly Sarti Wroblewski ‘02, director of infectious disease programs for the Association of Public Health Laboratories

MAJOR: Medical Technology

ADDITIONAL EDUCATION: Master of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University

HOMETOWN: Moosic, PA

CURRENT CITY OF RESIDENCE: Silver Spring, MD

FAMILY: Husband, Ed, and sons, Eddie, 8, and Calvin, 4

Kelly Wroblewski’s role in the pandemic response can be likened to that of a detective in a war zone. As a director in a public health network, she’s worked both quietly behind the scenes yet vocally on the frontlines. Her primary weapon has become the holy grail in this battle: the long-awaited COVID-19 test.

Wroblewski’s daily tasks differ from those of other scientific groups responding to a public health emergency. Public health laboratories, present in every state, monitor the collective health of the public and inform the care of the population rather than the individual. An organizational leader in the national network of public health labs, all of which were on high alert awaiting from the CDC the assay, or chemicals, that would detect the virus, Wroblewski and her crew have been first responders in another sense of the word. That’s because, in the early days of the virus, only public health labs were allowed to run testing. She became a vanguard, however, in getting all critically needed hands on deck.

Having begun her career at a microbiology lab at a small Pennsylvania hospital before taking a fellowship at the National Institutes of Health working on antimicrobial resistance then earning her MPH and working in the clinical lab at Johns Hopkins, Wroblewski has participated in many outbreak responses. So while COVID-19 is a novel virus it’s familiar ground for her.

She kicked her leadership into high gear after Jan. 18, the day on which the CDC detected the first case of the virus in the United States. Much of her role then was to work the phones furiously, assessing whether individual laboratories were ready with the necessary supplies and equipment once the assay was released and the labs could then “test the test,” so to speak, before themselves administering it.

Because of the now-well-known problems with the first released test and the initial prohibition on private labs doing testing, Wroblewski made an unprecedented move as the country awaited some positive news: She wrote to the FDA asking for permission for public health labs to make their own tests.

Because the first case in the United States with untraceable origins confirmed that COVID-19 had taken root here, the FDA essentially agreed, permitting advanced labs to develop their own tests.

This was a watershed moment for public health laboratories, and Wroblewski was at the forefront.

Royal News (RN): Kelly, it can be said that you are working in an epicenter of the fight against COVID-19. You recently told NPR that the situation with testing in America was “a giant mess” but that you were trying to remain optimistic that there was a light at the end of the tunnel. In the few weeks since you’ve spoken to NPR has the availability and effectiveness of the rapid test increased your optimism on the testing front?

Kelly Wroblewski (KW): The rapid molecular test is certainly another welcome tool in the toolbox, but, like many other testing supplies, there are limits to the availability of reagents, and it is not going to be the best fit for every setting. We continue to increase and improve capacity, but we still have room to improve both in terms of testing capacity and testing strategy. We are making progress, though.

RN: Early on, just after the virus hit the United States, the initial test fast-tracked by the FDA was considered glitchy at best, and it wasn’t until late February that a new test finally showed up. Can you tell us a little more about the mood in your sector during those waiting days?

KW: There was definitely an anxious vibe. We roll out and implement new tests with some frequency, and this had never happened. So there was a certain amount of disbelief and a lot of anxiousness as the public health laboratories waited for some resolution to the problem.

RN: Are the right people able to receive access to the rapid test right now? And, if not, who are the right people who should be receiving access?

KW: The rapid test has opened up testing, but it’s by far not accounting for the bulk of the tests being performed. The rapid test is really best used in settings where a there isn’t easy access to laboratory testing and a fast result is needed to inform decision making. Examples include places like rural critical access hospitals, nursing homes or prisons.

RN: What needs to change right now when it comes to testing?

KW: We need a high-quality, well-vetted antibody test. More than that, we need a thoughtful, feasible testing strategy that includes implementation details. Up to this point we’ve been so reactionary; we’ve been reacting to a new problem every day. We need to take the time to build plans with some scientific rigor behind them.

RN: Can you describe your emotions after you essentially got the ball rolling with the FDA so that public health labs could work independently on their own tests? We’d love to hear of your excitement as well as your fears.

KW: A few things happened at once. As they opened up the pathway for laboratories to develop their own SARS-CoV-2 tests, FDA and CDC also dropped the problematic component of the original CDC test. So in the end, most of the public health laboratories moved ahead with the CDC assay. My primary thought at the time was pushing to make sure public health labs brought a test on as expeditiously as possible. It was exciting to be involved in shaping policy in that way. I really look forward to the after action and thinking through how we use some of these actions to build a system that allows us to do better in the future.

RN: The testing landscape – at least in terms of who was allowed on the mat – essentially went from public health laboratories flying solo to private laboratories and eventually the private sector all contributing. What’s the next best step in this battle – for everyone involved in testing?

KW: We are going to need all hands on deck for a long time. It goes to what I said before about developing a thoughtful strategy. All of those laboratories from point-of-care testing sites to hospital labs to commercial labs to public health labs have a role they are best suited to play. Defining those roles and ironing out the logistics of getting the right specimens to the right labs is going to be key to ensuring we are using all of our laboratory resources most efficiently. It will be a critical component of this next phase.

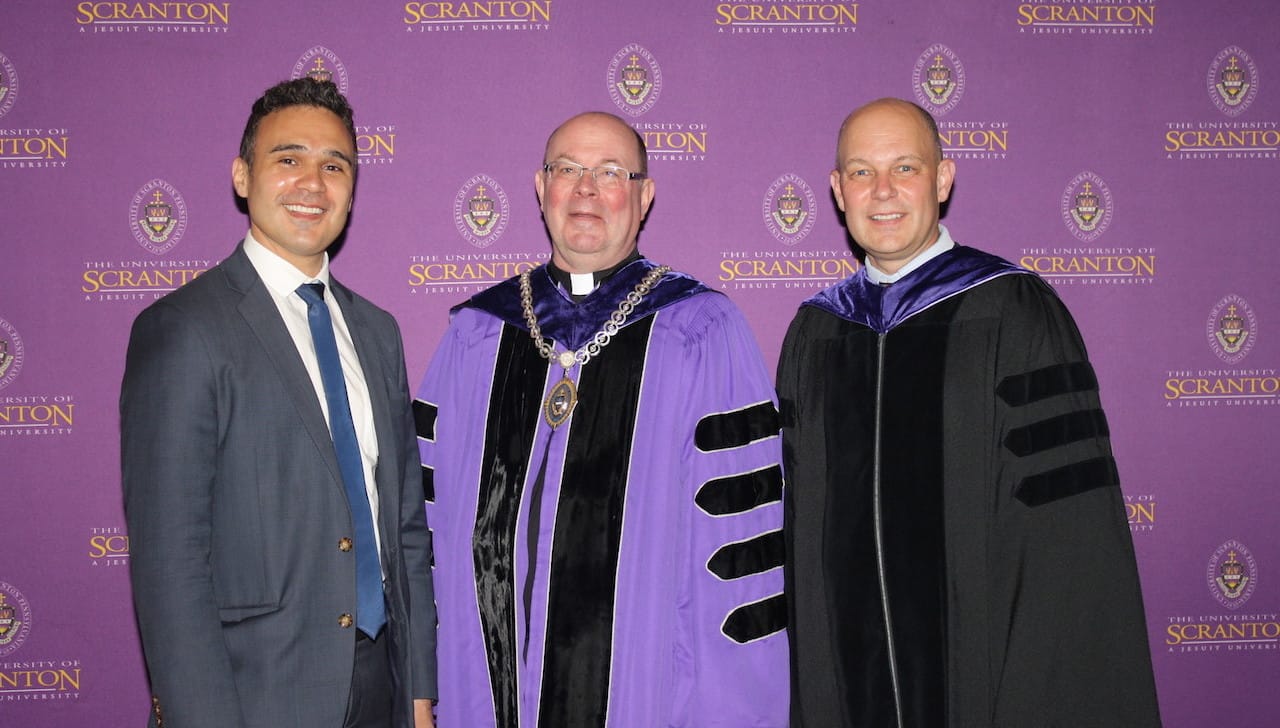

RN: Is this the fight of your life so far? Can you tell us how your Scranton education armed you for it?

KW: Someday, I am sure it will all sink in and I will feel that way. Really though, I’ve been taking it one day at a time, addressing the problem in front of me to the best of my ability and moving on to the next one. Scranton, for me, struck that perfect balance between being challenging and supportive. I never felt coddled and worked really hard. At the same time, I felt that my professors wanted the very best for me and therefore expected the very best effort out of me. It’s that sense that putting forward your best effort is going to yield good results.

Grace Okrepkie (pictured at left) is an occupational therapy first-year at the University. She is one student who feels the “togetherness” that Marinucci described.

Grace Okrepkie (pictured at left) is an occupational therapy first-year at the University. She is one student who feels the “togetherness” that Marinucci described.

Matthew Marcotte (pictured at left), a junior forensic accounting student at the University, found that the check-ins a reflection of the strength of this community.

Matthew Marcotte (pictured at left), a junior forensic accounting student at the University, found that the check-ins a reflection of the strength of this community.

Kim Subasic, Ph.D., MS, RN, CNE, interim chair of the Department of Nursing, has been hosting virtual coffee chats with the student nursing representatives in each cohort.

Kim Subasic, Ph.D., MS, RN, CNE, interim chair of the Department of Nursing, has been hosting virtual coffee chats with the student nursing representatives in each cohort.

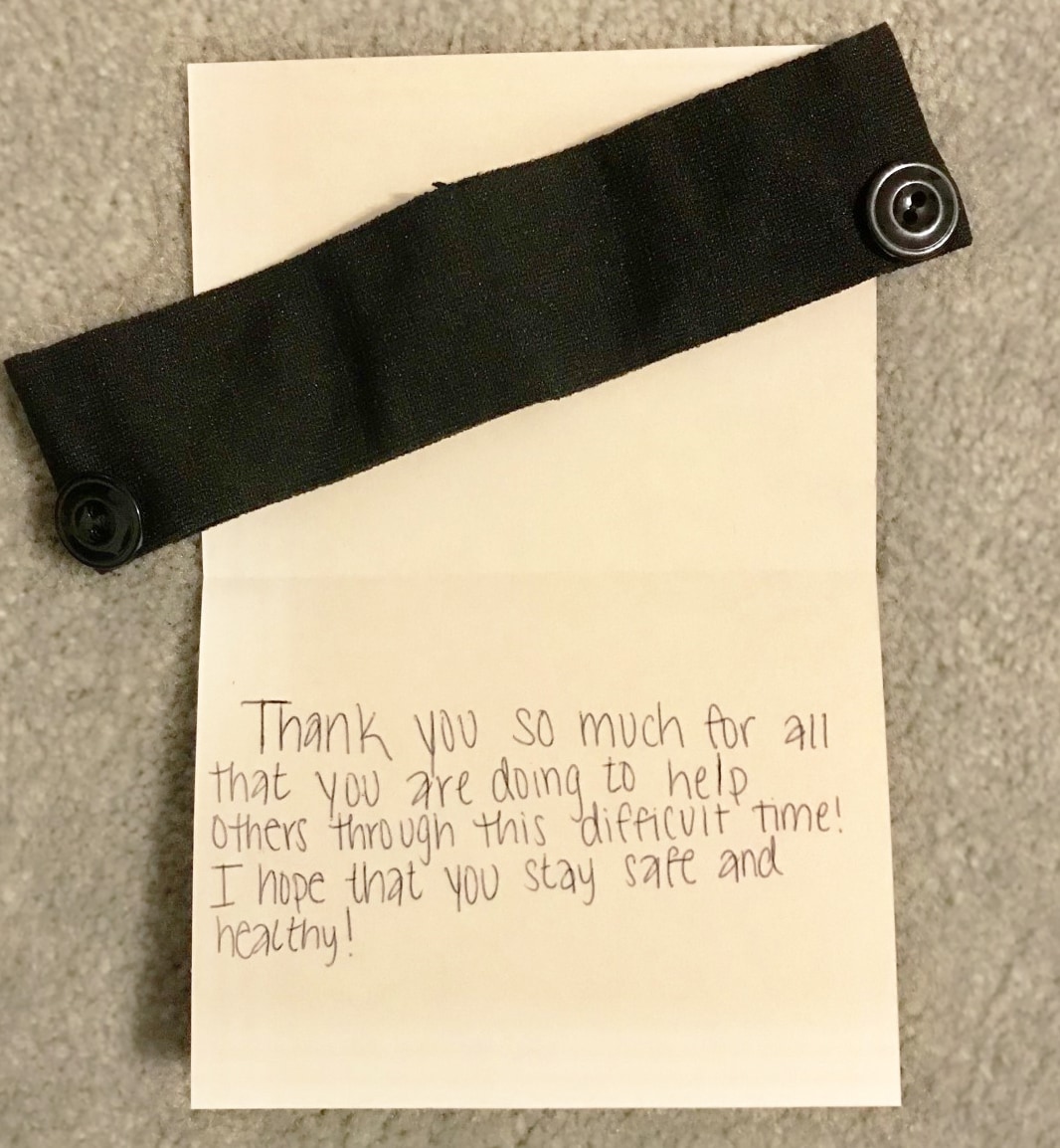

"My customers typically come to me for alterations, custom dresses, things that are wants rather than needs," she said. "So, while it's disheartening that our health care providers don't have what they need during this time, it's nice to be able to help."

"My customers typically come to me for alterations, custom dresses, things that are wants rather than needs," she said. "So, while it's disheartening that our health care providers don't have what they need during this time, it's nice to be able to help."